Inside the Mahamuni Paya, in the southern stretches of

Mandalay sits a 2000 year old Buddha statue, and everyday worshippers lovingly

press new layers of gold leaf onto every inch of its surface, save for the

face. The layers of gold, now about 15

centimeters thick, leave Buddha swollen with lumpy growths of gold tumors. Midas-itis.

The statue can only be seen through two narrow passages, so a TV screen

has been hung on a wall with a live feed of the gold pressing, so worshippers without

a direct view have a place to prostrate themselves before the image of Buddha.

In the passageways leading into the surrounding markets toil

an army of religious craftspeople. In one

stall a gong maker is testing tones and reshaping gongs that aren’t quite

right. Next to a room full of unfinished

marble Buddhas a metal worker is tracing lines into sheet metal: the ornate fiery

fringe that adorns so many buildings and relics being reduced to simple traces

before me.

A short bike ride up the canal from there had me squeezing

my way through a packed jade market, in a sprawl large enough to fill the city

block and flanked by probably thousands of parked motorbikes. Aside from the initial extraction, every step

of jade production was represented in one place. The first row featured long rows of raw jade,

from huge unfinished cuts down to swept up shards, all laid in piles for surveyors

to inspect with flashlights and magnifying glasses. Much like the fruit hawkers, the jade venders

kept their product shimmering with generous splashes of water. Down the way, an endless row of young men

using pedal operated grinders to smooth rough jade into their desired shapes,

and on the far end of the market, the finished product: rings, pendants, bracelets,

and lovely statues, all made of jade.

The city palace sits in a perfect square wrapped with an

imposing moat, totaling at least 10 kilometers in length. The ominous repetition of turrets and

quantities of time it takes to circle the palace grounds set high expectations

for what’s inside, but after security permits you into the walls it’s hard not

to be somewhat underwhelmed. The vast courtyards

don’t permit foreigners to explore, but the state of neglect throughout discourages

the thought. The palace itself is fairly

impressive, but merely a reconstruction of the original, having been destroyed in

the fighting between Japanese against English and Indian forces in World War

II. I spent more time admiring a case of

the king and queen’s jewel encrusted betel spittoons than anything else.

Hovering over the palace to the north is Mandalay hill,

overlooking the otherwise flat city. A

stepped concrete path leads to the top and a pair of colossal nat guard the

entrance, warding away evil spirits and signaling the ground as a holy place (nat

are spirits from pre-Buddhist animist cults, now absorbed into a few version of

Buddhism; in this case they look like scary dog-lions). You have to leave your shoes at the entrance

to proceed to the top, where a towering standing Buddha waits for you, pointing

at where one day a great city would be built.

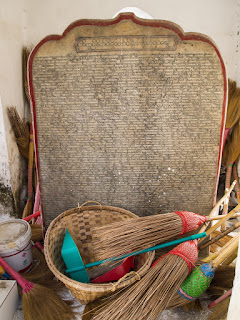

Seven hundred and twenty nine whitewashed pagodas orbit

Kathodaw Paya at the base of the mountain.

Each pagoda houses one giant stone slab etched in tiny Burmese script:

Buddhist literature, the total of which boasts to be the largest book in the

world. While I was there, one of the

pagodas also housed a young couple making out tenderly, with a leering peeping

tom hanging onto the edge. He shot me a

violent sneer warning me not to give him away .

Outside the gate a lady waits with a birdcage, offering visitors a

chance to pose with a bird in hand before sending it sailing away into the air

triumphantly. It’s a seemingly lovely

sight until you notice that every other bird chucked skyward floats drunkenly

into the side of a wall to certain injury – maybe death – and that every bird

in the cage is drugged to placidity enough to sit calmly in a human hand.

That night I thumbed out some extra kyat to see a show

(where the hell did all my money go? I have to change money again?).

The Moustache Brothers – only two of the three are in fact mustached –

received international attention when two of them were jailed for making a joke

about the military regime at a show for Aung San Suu Kyi, and again for

illegally giving food to monks at a demonstration. The brothers are now free, but it is illegal for

any citizen to employ them, so they run the show out of their own home in

English to tourists. It was in the

format of a traditional Burmese vaudeville show with a generous helping of

political satire, featuring folk dancing, slapticky stand up, and video clips

of mostly American celebrities voicing their concern and support for

Burma. Lu Maw was the only brother with

English enough to run the show, and his wife had a fair amount of stage time

demonstrating dances she spent years perfecting. She had one of those odd permanent smiles

that seemed like it wouldn’t falter even in child labor. The show was interesting enough, but I found

myself coloring the show more positively because of their history and bravery

in face of the government; without those qualities, I think I would have interpreted

the show as rubbish. Burmese humor doesn’t

seem to translate well to English, the show lacked any of the polish you’d

expect from a family of lifelong entertainers, and the performers all seemed

tired, passionless, and past their prime.

I think everyone – excluding the government – would be happier if the

show was in Burmese for Burmese.

The name Mandalay evokes images of exotic tropical

loveliness to the western ear, but that’s because of a stupid casino that has

nothing to do with Myanmar. Ultimately

Mandalay proves to be a pretty typical Asian city, a noisy dusty sprawl of

cheap apartment buildings without much to make it unique to itself. In one packed day, I’ve done what seems to be

just about everything there is to do for a visitor, and I’m looking forward to

moving on.

No comments:

Post a Comment